What is media ecology?

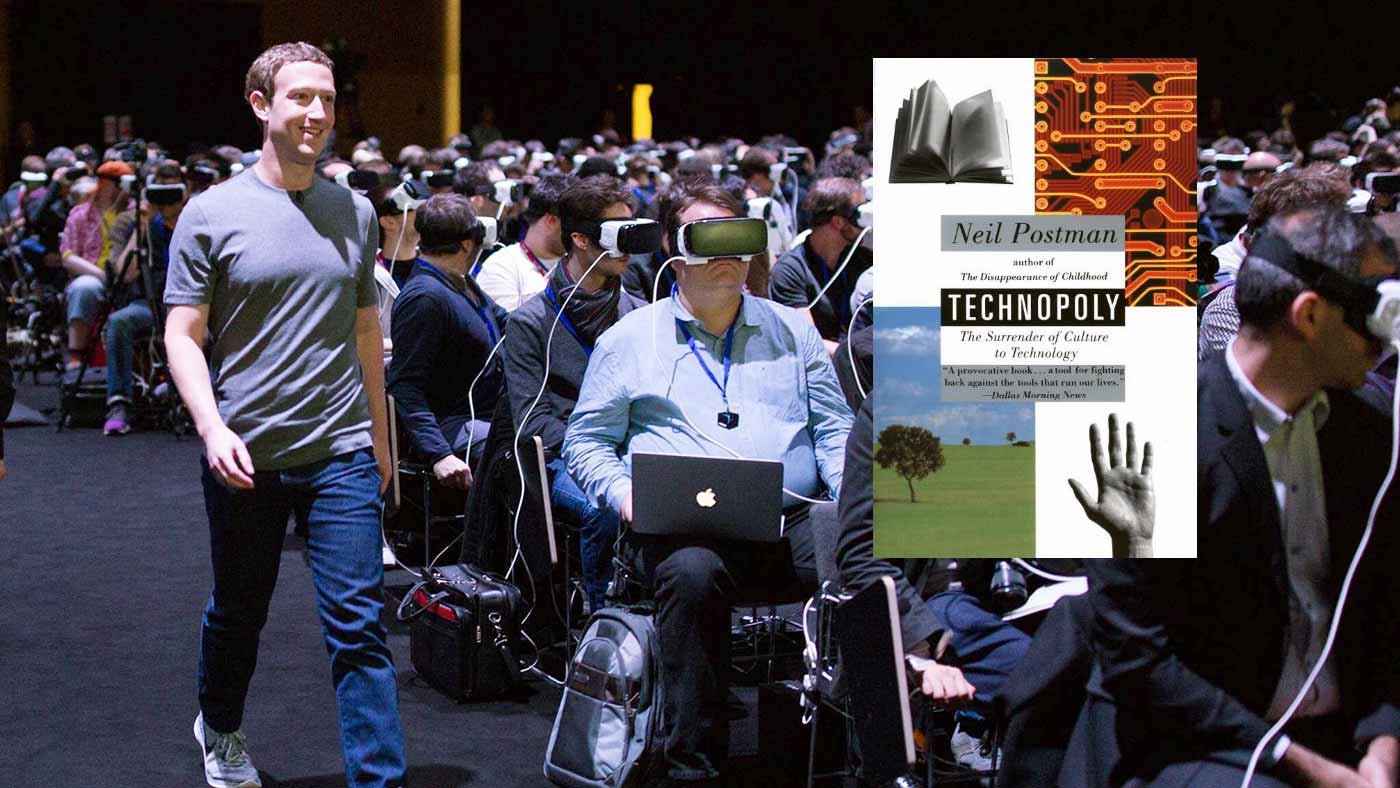

Have you ever heard the term “media ecology”? Do you know what it means? Ever since learning about it, thanks to the brilliant late author Neil Postman, its definition has informed how I view every mass medium – from radio to TV, to the internet and every technological change that has emerged in the past decade.

According to the Media Ecology Association:

Media ecology looks into the matter of how media of communication affect human perception, understanding, feeling, and value; and how our interaction with media facilitates or impedes our chances of survival. The word ecology implies the study of environments: their structure, content, and impact on people.

“A new technology changes everything”

If you still think this definition is a bit esoteric and vague, I think Neil Postman described it best in his book Technopoly (1992):

Technological change is neither additive nor subtractive. It is ecological. I mean “ecological” in the same sense as the word is used by environmental scientists. One significant change generates total change. If you remove the caterpillars from a given habitat, you are not left with the same environment minus caterpillars: you have a new environment, and you have reconstituted the conditions of survival; the same is true if you add caterpillars to an environment that has had none. This is how the ecology of media works as well. A new technology does not add or subtract something. It changes everything.

It’s crucial to keep this in mind when thinking about the “metaverse” and Mark Zuckerberg’s announcement in late October 2021 about his company’s laser focus on virtual worlds and merging the real world with virtual reality – to the tune of 10 billion dollars a year in investments.

Monetizing our meta-data

Writer Nicholas Carr astutely observes:

Two of the most revealing, and unsettling, moments in Zuckerberg’s keynote came when he was describing work now being done in the company’s “Reality Labs.” (Does Facebook have a Senior Vice President of Dystopian Branding?) He showed a demo of a woman walking through her home while wearing a pair of Meta AR glasses. The glasses mapped, automatically and in precise detail, everything she looked at. Such digital mapping will allow Meta to create, as Reality Labs Chief Scientist Michael Abrash explained, “an index” of “every single object” in a person’s home, “including not only location, but also the texture, geometry, and function.” The maps will become the basis for “contextual AI” that will be able to anticipate a person’s intentions and desires by tracking eye movements. What you look at, after all, is what you’re interested in. “Ultimately,” said Abrash, “her AR glasses will tell her what her available actions are at any time.” The advertising opportunities are endless.

He continues:

If Facebook’s ability to collect, analyze, and monetize your personal data makes you nervous now, wait till you see what Meta has in store. There are no secrets in the metaverse.

So, when reading or discussing Facebook’s – well, Meta’s – grand views of the next years to come and the potentials of the “metaverse”, please keep Neil Postman’s words in mind: “A new technology does not add or subtract something. It changes everything.”

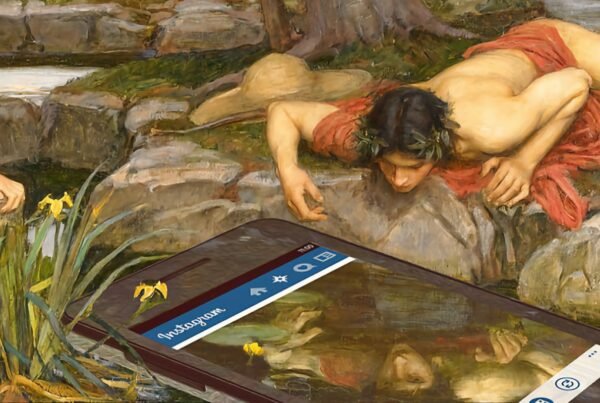

Is the “real world” in such dire shape that we must spend enormous amounts of time (and money) to escape to a virtual world that we can make our own? A virtual world owned and controlled by a company that thus far has made nearly all its money from advertising?

How will our relationships, friendships, work lives be affected by the metaverse?

Isn’t it ironic that the term itself – “metaverse” – was coined by writer Neal Stephenson in his dystopian novel Snow Crash?

Don’t be fooled by splashy presentations and enthusiasm about new technological tools. When in doubt, I’d highly recommend reading Postman’s aforementioned book Technopoly. And Nicholas Carr’s blog series “meanings of the metaverse.”