photo by: Daniele Franchi (Unsplash)

New technologies compete with old ones—for time, for attention, for money, for prestige, but mostly for dominance of their world-view. This competition is implicit once we acknowledge that a medium contains an ideological bias.

– Neil Postman, Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology

What is the ideological bias of social media platforms? I’d venture to say that premium value is put on the present, the now. A post or a video that was popular 5 days ago is seen as old news today. Irrelevant. Passé. Moving on to the next cool thing.

I think social media platforms by design glorify the now. And consequently, the past – even the recent past – is considered not worthy of our attention. It’s as if, since the rise of social media, we’ve been conditioned to value the present and dismiss the past. We’ve been trained to feel this way for years – for a decade or more, I dare say – since many of us have been spending many minutes (or hours) on social media platforms every day for years.

The reason for the emphasis on the present is that it encourages people to post frequently and to spend lots of time on social media platforms. The more time they’re on, the more ads they can potentially see and the more the algorithm learns about what makes them tick. I explored this issue in last week’s post “The pressure to be popular is purely for profit.” It’s all about the algorithm!

Thing is, I’m a little saddened over what we are missing out by focusing so much on the present and the future. Propose watching a classic film from 1963 to a friend and they may give you an eyeroll and say “why, that’s so old!” (Never mind a film from 1927 – say, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis which is a MASTERPIECE – but I’m going off track.)

Have you noticed that when something is popular on a streaming platform, it seems like everyone is watching it, so they will be able to discuss it? This study about Netflix originals is illuminating:

Netflix original series generate a lot of hype for the streaming service but after the initial surge in viewership they supply, subscribers lose interest quickly. That’s according to new research from media analyst company MoffettNathanson, which dug into Nielsen’s U.S. streaming data to get a clearer picture of how Netflix’s massive content budget is reflected in engagement. The company found that Netflix had 40 original shows that reached Nielsen’s top 10 list during the third quarter, but that none of them accounted for more than 1.5% of time spent on Netflix in the U.S. “This suggests that Netflix will need to continually refresh their original content pipeline to keep viewers engaged as they move from one original series to the next,” wrote Michael Nathanson in a research note.

Luckily books don’t seem subjected to the same fate. But films! There are so many gems hidden from the public because there is so much focus on the now. Ditto for music, I’d venture to say.

In our current economy, we are encouraged to produce, produce, produce and consume, consume, consume a constant stream of fresh content.

Have you noticed how social media platforms don’t have an easy way to see old posts?

For instance, Twitter could have a sidebar allowing users to browse old posts by month and year. Instead, if we are interested in seeing what someone wrote in the past, we either have to keep scrolling down their feed and click on “Load more.” Or we could use advanced search and enter a date range, but Twitter isn’t making this any easy.

For Instagram, if you want to see someone’s old posts, you have to go to their profile and keep scrolling down. There is no visual representation of dates on the feed, so to know when something was posted you have to click on a photo and check out the date. Because it’s so visual, there is no easy way to search for specific content using words. You can’t search captions. And you most certainly can’t search by date.

TikTok allows creators to pin 3 items of content to the top but there is no way to quickly see when something was posted or to search inside someone’s captions.

The lack of these features is intentional. It increases time spent on the platforms – which is incredibly valuable for their pockets and in the eyes of their investors.

Dominic Basulto wrote about this very issue for BIG THINK: “The Internet’s Cult of Now”:

There is only one measure of time that matters to the current Internet generation: the here and now. The Cult of Now is influencing everything that we do and every interaction we have on the Internet, especially since providing a live, real-time update is often no more difficult than pressing a button on a smart phone. We now perceive our digital lives as a continuous flow of information, and as the intensity of this information flow builds, it means that “the now” gets a disproportionate amount of attention and focus in our society. The Cult of Now satisfies our desire for instant digital gratification, but does it impoverish us in other ways?

Does it matter when Basulto wrote this? Because his article was published on March 28, 2012. Yes, you read that right, 10 YEARS ago. Has his take lost value and your respect because of the date when it was published? It would make my point, you know?

Neil Postman wrote in Technopoly:

On the one hand, there is the world of the printed word with its emphasis on logic, sequence, history, exposition, objectivity, detachment, and discipline. On the other, there is the world of television with its emphasis on imagery, narrative, presentness, simultaneity, intimacy, immediate gratification, and quick emotional response.

When was Technopoly published? In 1992. Yes, 30 YEARS AGO! And it’s still incredibly relevant today.

Postman writes about TV’s focus on:

- imagery

- narrative

- presentness

- simultaneity

- intimacy

- immediate gratification

- quick emotional response

Doesn’t this make you think of the internet, too? Of Twitter, TikTok, Instagram? What are we losing by immersing ourselves fully in this world?

Postman said it: logic, sequence, history, exposition, objectivity, detachment and discipline.

Time to remember how lucky we are to have 2 millennia worth of culture – centuries of extraordinary books and music and more than 100 years of superb films – to dive into.

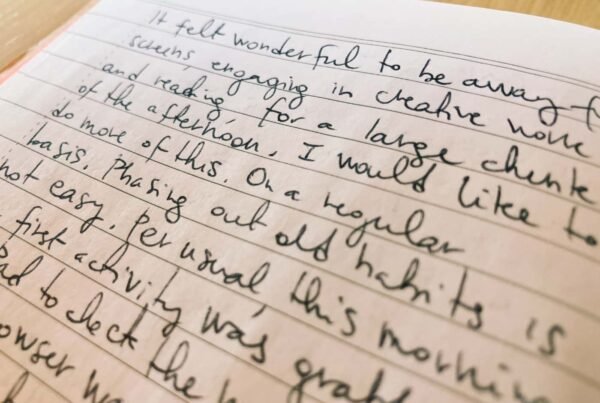

Time to reconsider what we value. Time to go offline and focus on the real.