This essay is the second post in a series about ad tracking. If you missed the first post, read it here: “Show Me Your Ads”.

I will never forget the first time I was really creeped out by the invasiveness of online advertising. It’s when I got confirmation that Instagram spoiled the surprise of my fiancé’s proposal.

Out-of-character ads

Early October 2018. I was sitting on a plane in Frankfurt, Germany, waiting for the doors to close; it was my second flight of the day: I had been invited to screen and discuss my documentary The Illusionists in Trondheim, Norway and I had two connecting flights: one in Frankfurt and another in Oslo. I had been up since 5am to make my first flight. At the time I was still using Instagram daily, on my main phone. When I opened the app in Frankfurt and scrolled through the main feed I saw an ad for an engagement ring. And then another.

This was so odd and uncharacteristic: my friends and family know I am not into jewelry – AT ALL. If I had a thousand Euros (or more) to spend on a luxury item, I would steer away from rings and handbags; I would be immediately drawn to photographic equipment instead. A prime lens with a 1.2 aperture is far more appealing and valuable to me than any precious gemstone.

At the time I had been researching the world of online advertising and surveillance capitalism for the sequel of my documentary The Illusionists. So the ads for an engagement ring – again, absolutely uncharacteristic – made me suspect something may be up with my then boyfriend. I didn’t bring this up with him, but it was definitely in the back of my mind.

The Proposal: connecting the dots

My boyfriend (and spoiler: now husband) proposed during a vacation in Tuscany in late November 2018. He told me he had taken advantage of my trip to Norway to go buy the engagement ring. It amused him that the ring box had been sitting in a clear container with his stuff in our bedroom for 7 weeks… without me noticing it. I told him about the strange engagement ring ads I had been seeing on my Instagram feed during my trip to Norway. My then fiancé said that the morning of my departure he had been researching engagement rings and where to buy one.

Meta (the parent company of Instagram) definitely knew about our connection: we lived in the same location, used the same wireless router to connect to the internet and exchanged numerous WhatsApp messages on a daily basis (an app also owned by Meta). How creepy it is that he searched on his cell phone for jewelry stores and engagement rings… and the same morning, more than 500km away, I saw ads for engagement rings on my Instagram feed.

You may think it’s a fluke but I haven’t seen ads for jewelry anymore on Instagram after this. Not even once.

Invasive Ads

After last week’s post, a friend went on Instagram to see which kind of ads the app displayed for them… and then sent me this message:

“what’s really funny is I just said luxury hotels in the Alps and opened Instagram now (thinking hmm, I wonder if any funny ads today) and this appears as the first one.“

The text reads (emphasis mine): “____ is a unique ultra-luxury vacation home in the Austrian Alps, midway between Salzburg and Kitzbühel“

Screenshots of the text exchange with my friend and the ad they saw on Instagram. Shared with permission from them.

Why Should We Care About This?

You may be wondering: why should I care about this? Nobody got hurt – the consequences of ad tracking are harmless.

Think again.

As I mentioned last week, invasive ad tracking can do a lot of damage to vulnerable people. It’s been well documented how Big Tech can easily infer when a woman is pregnant… and shows her countless ads for pregnancy and baby products… and keep showing these ads even after the woman suffered pregnancy loss – which is devastating and heartbreaking.

This happened to Gillian Brockell. CNBC covered this agonizing issue in December 2018:

At one of the saddest times of her life, Gillian Brockell kept seeing ads on social media that twisted the knife in her wound. In an open letter posted to Twitter and addressed to “Tech Companies,” the Washington Post opinion video editor says she continued to be targeted with motherhood ads after learning that her baby would be stillborn. At a time when the public is questioning tech companies’ hyper-specific ad targeting, Brockell’s letter highlights the damaging emotional effects this practice can have when these companies fail to adjust their targeting to new information about someone’s altered life situation.

If you see ads that are triggering to you, the website Tommys shows a step-by-step guide about how to turn off advertising about a specific issue (in this case it’s pregnancy loss, but it can be used for other topics, too).

Something related to this recently happened to a friend of mine, so I am particularly touchy about this issue. It would make my blood boil to think she may be seeing maternity ads after the traumatic loss she suffered.

Auditing Our Privacy Settings

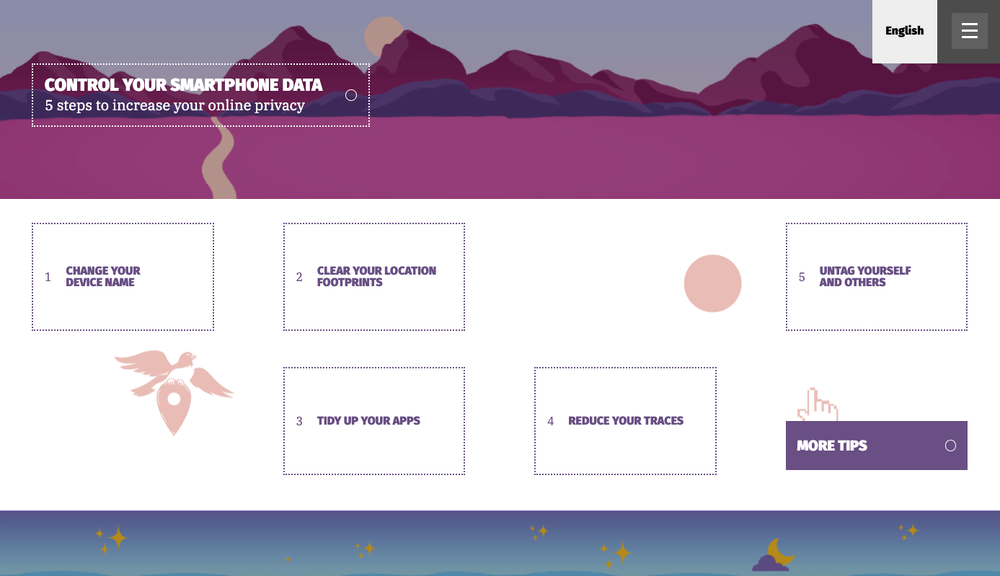

While researching this topic and activists resisting surveillance capitalism, I stumbled upon the work of writer and educator Safa Ghnaim, who spearheaded the initiative Data Detox Kit.

The project’s website offers numerous tools for education and protection of one’s own privacy:

Take control of your digital privacy, security, and wellbeing, protect the environment, tackle misinformation, control your health data, find resources for youth and families, browse our Alternative App Centre and workshop materials

a screenshot from the website of Data Detox Kit

I’m super careful about my online footprints, regularly use a VPN, ad blockers, a DNS firewall – and I’ve put apps by Meta on an empty “burner phone” with a different Apple ID. And yet! My main phone readily identifies me when I am out in public – it’s called “Ele’s iPhone (model number)”. The top advice from Safa Ghnaim is to change your device name:

At some point, you may have “named” your phone for Wi-Fi, Bluetooth or both – or maybe the name was automatically generated during setup. This means that “Alex Chung’s Phone” is what’s visible to the Wi-Fi network owner and, if your Bluetooth is turned on, to everyone in the area who has their Bluetooth on as well. You wouldn’t announce your name as you enter a café, restaurant, or airport, so neither should your phone.

I’ve just renamed my iPhone after my favorite cartoon character… followed by the word “device” (no phone maker or model number anymore!)

As always, thanks for being here.